Manon Lescaut: Sandra López; the Chevalier Des Grieux: Matthew Vickers; Lescaut: Filippo Fontana; Geronte: Costas Tsourakis; Conductor: Victor DeRenzi; Stage Director: Stephanie Sundine; Scenic Designer: David P. Gordon; Costume Designer: Howard Tsvi Kaplan; Lighting Designer: Ken Yunker; Chorus Master: Roger L. Bingaman

Giacomo Puccini’s Manon Lescaut (1894) had much going against it from the start. His previous operas had been lukewarm forays, not exactly successes. A previous (and successful) version, Manon, had been completed just 10 years previous by Jules Massenet. Puccini kept changing librettists and in the end nobody even wanted their name on the opening program. He pared down the plot of Abbé Prévost’s novel Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut so much that even today, audiences scratch their heads over its awkward transitions and strange omissions. For some reason, he concentrates all of the gaiety in acts one and two, and all of the gloom in acts three and four.

But in the end, very little of this matters. Nineteenth century operas are rarely strong arguments for sterling plot creation. Later in life, Puccini did improve significantly, as any opera fan can see from his last and greatest opera Turandot (that of Luciano Berio’s ending, not Franco Alfano’s). The Sarasota Opera performance dives gleefully into ML’s optimistic first act and beautifully conveys the spirit of youthful infatuation. As Des Grieux, Matthew Vickers pours out his feelings beautifully in the famous soliloquy “Donna non vidi mai,” made famous by Enrico Caruso and attempted by every other tenor since. As Manon Lescaut, Sandra López sings her brilliant and joyous aria while living with the libertine Geronte,“Lora, or Tirsi.” The audience suddenly senses it’s not going to go on forever.

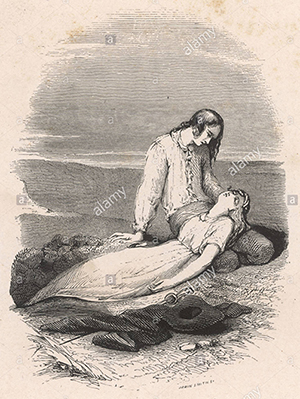

Much creativity and planning went into the three stage settings. While done in period style, the opening village street scene is kinetic rather than static, buzzing with life, and the resulting intrigue is exciting from the start. In Act II, as Manon luxuriates in her mansion with Geronte, the very walls cry out “nobility.” But the final act in the Louisiana desert (don’t ask how they got there) is most stunningly well designed. A huge twisted fallen tree in the foreground underscores the twists and turns that their love affair has taken and contrasts with the gloriously ruddy sunset behind them. Dense emotional expression is reached in the final duet between Manon and Des Grieux. In “Tutta su me ti sposa,” Manon succumbs to grief and despair, realizing how her selfishness has brought tragedy upon her and her lover. As Geronte, Costas Tsourakis is the right kind of vile and cursed scoundrel. Filippo Fontana’s Lescaut is convincing as an unreliable ally, shifting his loyalties back and forth.

The orchestra – through the tidy wand of conductor Victor DeRenzi – showed its skill in the Act III instrumental “Intermezzo,” which is one of Manon Lescaut’s most unusual features. Why does it even exist? Good question. Some believe that it abstractly conveys Manon’s sentencing and her transportation to Le Havre. Seems plausible. Toward its conclusion it grows tempestuous and seems to careen toward disaster. But it avoids tragedy and lulls us with a descending motif that deceptively shimmers with hope. However, as clever as the device is, it’s a bit subtle for the uninitiated. In later years, Puccini made sparse use of such lofty intermezzi (Suor Angelica, 1918). Perhaps he realized that straight plotting conveyed emotions more efficiently?

So is Manon Lescaut “grand opera?” Not quite. But parts of it are pretty good. In focusing on the show’s highlights, like the inherent spectacle of the lovers’ plight, the Sarasota Opera made us realize that its cracks & flaws, Puccini’s youthful “experiments,” were not really that big a deal.